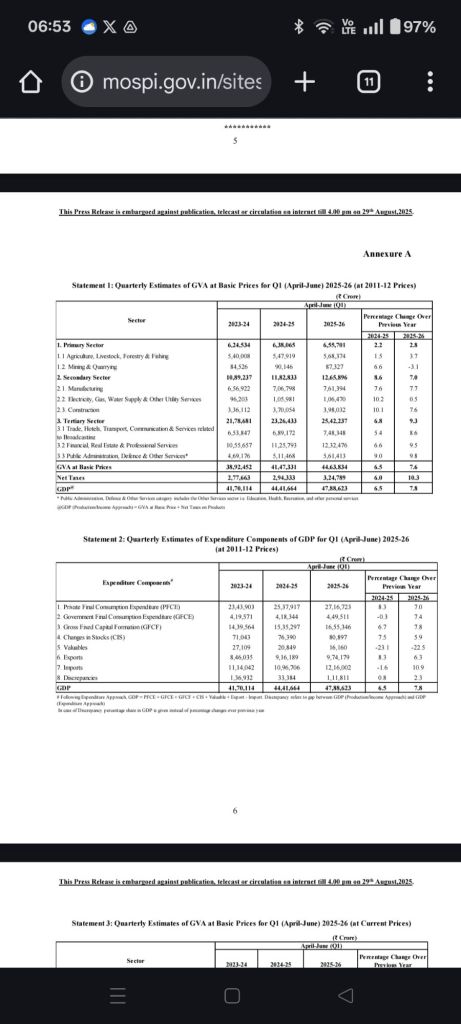

The newest national accounts offer an easy headline and a harder truth. Real GDP in Q1 FY26 rose 7.8% year-on-year and real GVA 7.6%—a clean step-up from last year’s 6.5%. Net taxes on products climbed by around 10%, so GDP outpaced GVA, a sign of buoyant formal activity and indirect-tax collections. The economy is not stalling. But look beneath the hood and you find a recovery leaning heavily on services and the state, while the mass-employment engines show less spark than the headline suggests.

The anatomy of growth

Start with the sectoral mix. Agriculture did better—about 3.7% versus 1.5% a year ago—supporting rural cash flows. Mining, however, shrank roughly 3.1% after expanding last year, trimming the primary sector’s contribution.

The secondary block tells the more important story for jobs. Manufacturing expanded by about 7.7%, essentially unchanged from last year’s 7.6%—respectable, not re-accelerating. Construction, a cornerstone of urban employment for semi- and unskilled workers, slowed to roughly 7.6% from 10.1%. Utilities growth collapsed to about 0.5% from double digits, hinting at pricing and input frictions and offering little cyclical impulse. Put together, the secondary sector cooled to ~7.0% from ~8.6%.

By contrast, services re-took the baton. Trade, hotels, transport and communications strengthened to ~8.6% from ~5.4%—a welcome lift for contact-intensive, city-based work. Financial, real-estate and professional services surged to ~9.5% (from ~6.6%), while public administration and defence stayed near ~9.8%. Tertiary GVA overall quickened to ~9.3%. This is the backbone of the Q1 print: formal, higher-skill services plus government services.

The demand lens

On the expenditure side, the rotation is equally clear. Private consumption (PFCE) grew ~7.0%, slower than last year’s ~8.3%—not a collapse, but a downshift for broad household demand. Government consumption reversed last year’s contraction, growing ~7.4%, and fixed investment (GFCF) improved to ~7.8% from ~6.7%, consistent with public capex and pockets of private spending.

Two more lines deserve attention. First, valuables fell about 22.5%, often read as softer gold demand—good for the external balance, typically aligned with restrained mass consumption. Second, imports jumped ~10.9% while exports rose ~6.3%, worsening the net-exports drag. Without the commodity breakdown we cannot apportion this surge; if it is electronics and gold, it points to top-end demand, if crude and capital goods, it is more price and investment driven. Either way, the external account did not help growth.

Why the composition matters

India’s growth engine remains services-first. That suits the country’s comparative advantages and boosts tax buoyancy, yet it also risks widening the skill premium if manufacturing and construction don’t keep pace. Q1 did little to change that balance: one mass-jobs lever slowed (construction), the other was steady, not stronger (manufacturing). The offset came from trade/transport/hospitality, which did improve and will show up in shifts and gig hours. But without a construction upswing, the ladder from the informal edge to stable urban incomes is shorter than the headline suggests.

On demand, a combination of slower consumption, stronger investment, and higher imports is not unhealthy in itself—investment-led growth is exactly what policymakers have targeted. The question is breadth. When household consumption decelerates while the most dynamic sectors are formal services, it is prudent to ask whether growth is being felt evenly across income tiers and geographies. That is not an ideological worry; it is a macro one. Broad-based demand is what keeps a long cycle resilient.

The policy stance that fits the data

First, keep the capex pedal down—but crowd in the private side. Clear municipal balance sheets faster, release MSME contractor dues on time, and reduce working-capital frictions in public procurement. If investment is the driver, make it more labour-using.

Second, re-ignite construction. Fast-track approvals in housing, unlock stuck urban infrastructure, and align credit channels for small builders and allied trades. Few sectors convert rupees into semi- and unskilled jobs as quickly.

Third, widen manufacturing’s diffusion. Beyond marquee schemes, double down on labour-intensive lines—apparel, footwear, food processing, light engineering—with logistics fixes and targeted trade arrangements. Combine this with a compliance-light regime for micro-manufacturers so they can scale into the formal net without drowning in it.

Fourth, support the mass market without blunt stimulus. Calibrate rural support to monsoon outcomes; avoid broad giveaways, but remove pinch points—such as small-ticket credit for two-wheelers or working capital for kirana supply chains—where risks are manageable.

What to watch next

Three gauges will reveal whether Q1 was a staging post or a warning light: (1) cement dispatches and steel long-product output for a read on construction; (2) diffusion indices in PMI/IIP to see if manufacturing breadth improves; and (3) mass-market volumes—two-wheelers, entry-tier smartphones, FMCG units—rather than value sales alone. Pair these with the import composition and the picture will clarify quickly.

The verdict

Q1 FY26 is a good growth number built on an unbalanced mix. Services and the state delivered; construction cooled and manufacturing merely held its line; household consumption eased; imports ran ahead of exports. None of this argues for alarm. It argues for broadening. The task for the next three quarters is to convert fast GDP growth into felt growth—more sites breaking ground, more shop floors humming, and more households confident enough to spend without leverage. That is how a promising start becomes a durable expansion.