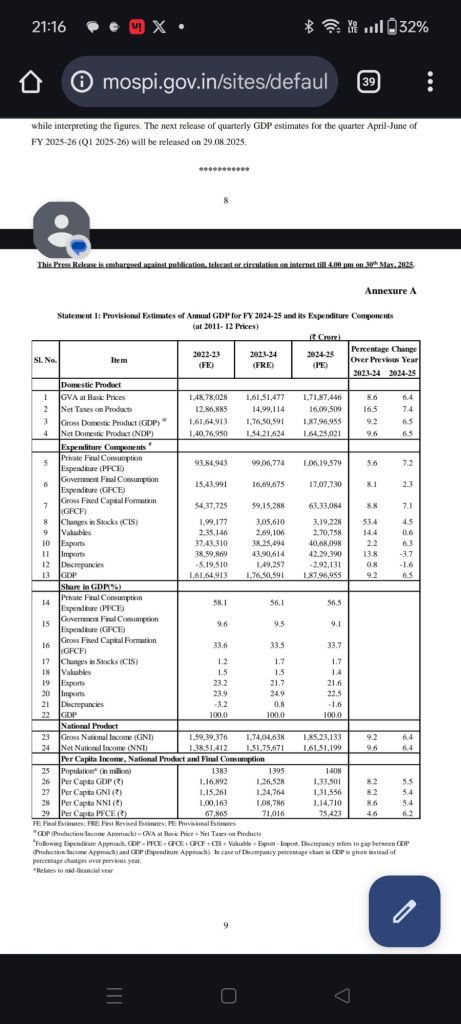

India’s economy expanded by 6.5% in FY 2024–25, down from 9.2% the previous year. While this growth rate remains one of the fastest globally, the moderation signals the end of the post-pandemic rebound and a transition into a phase where structural strengths and weaknesses will more clearly define the economic trajectory.

The composition of growth tells a layered story. Private consumption has strengthened, buoyed by easing inflation and a gradual revival in rural and urban demand. Yet, the sharp cutback in government expenditure suggests a more cautious fiscal policy, aimed likely at consolidating public finances but at the cost of reduced short-term stimulus. This balancing act between fiscal prudence and demand management will remain a delicate one in the months ahead.

Investment growth, though positive, has lost some momentum compared to last year. With global financial conditions tight and geopolitical uncertainties high, sustaining private sector capital formation will require persistent effort — including regulatory simplifications and incentives for domestic manufacturing. The manufacturing sector, in particular, which showed strong growth last year, has cooled. Its slowdown points to deeper structural constraints that India has long grappled with: scale inefficiencies, export competitiveness, and supply chain challenges. It remains to be noted that after agriculture this is the second most people intensive sector.

Meanwhile, the services sector continues to be a reliable driver, but signs of moderation here as well suggest that India cannot rely indefinitely on services-led growth. The construction sector, one of the few bright spots, reflects the ongoing emphasis on infrastructure building, but questions remain about whether this alone can compensate for weakness elsewhere.

The external sector has provided some relief, with exports showing better growth than last year. However, with the global environment still volatile, trade cannot be seen as a dependable engine without broader diversification and resilience strategies.

Importantly, per capita income growth has also slowed. For a country at India’s stage of development, steady and broad-based income growth is critical — not just for economic metrics, but for social stability and aspirational momentum.

India’s growth numbers, taken in isolation, are still respectable. But as the economy enters a post-rebound phase, the real tests lie ahead. Future growth will require deep reforms, not merely cyclical recoveries. Labour market challenges, skilling deficits, manufacturing bottlenecks, and the need for innovation-driven industries are not new challenges, but they are becoming more urgent.

As the rebound effect fades, India must now confront reality: sustaining high growth rates will demand a shift from consumption- and services-driven expansion to a more investment led growth model. The window for easy gains is closing. What remains is the harder, but necessary, work of building an economy resilient enough to meet the aspirations of its people and withstand the uncertainties of a changing world.