Caste has always been a crucial determinant in Indian politics, and the state of West Bengal is no exception. With a substantial Scheduled Caste (SC) population, the political dynamics of the state are heavily influenced by caste factors. Though West Bengal’s political discourse has traditionally been dominated by class-based narratives, especially during the rule of the Left Front, the past decade has witnessed a significant shift towards caste politics. The rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the decline of the Left have contributed to the growing prominence of caste-based identities in political mobilization.

This article provides an in-depth analysis of caste politics in Bengal, focusing on the SC population distribution, the socio-political challenges faced by SC communities, the urban-rural divide, and how caste has influenced recent electoral outcomes, especially in the 2021 Assembly elections.

The Significance of SC Population Distribution in West Bengal

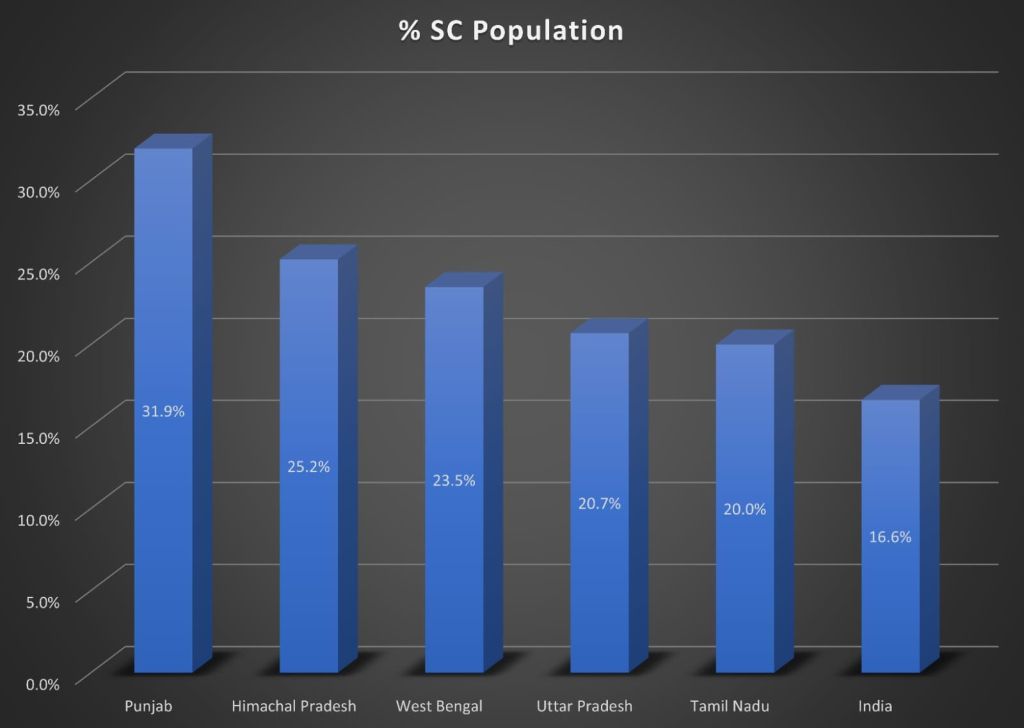

Scheduled Castes comprise 23.5% of the total population in West Bengal, making them an influential demographic group. This is significantly higher than the national average of 16.6%. Other Indian states with large SC populations include Punjab (31.9%), Himachal Pradesh (25.2%), and Tamil Nadu (20.0%). The relatively high percentage of SCs in West Bengal positions them as an important constituency in the state’s political landscape.

Despite their numerical strength, SC communities in Bengal have historically been marginalized, both socially and economically. This marginalization is deeply rooted in Bengal’s history and has long-lasting implications for the political and social empowerment of SC groups. For political parties in the state, understanding the complexities of SC communities’ socio-economic conditions, as well as their voting patterns, is crucial for electoral success.

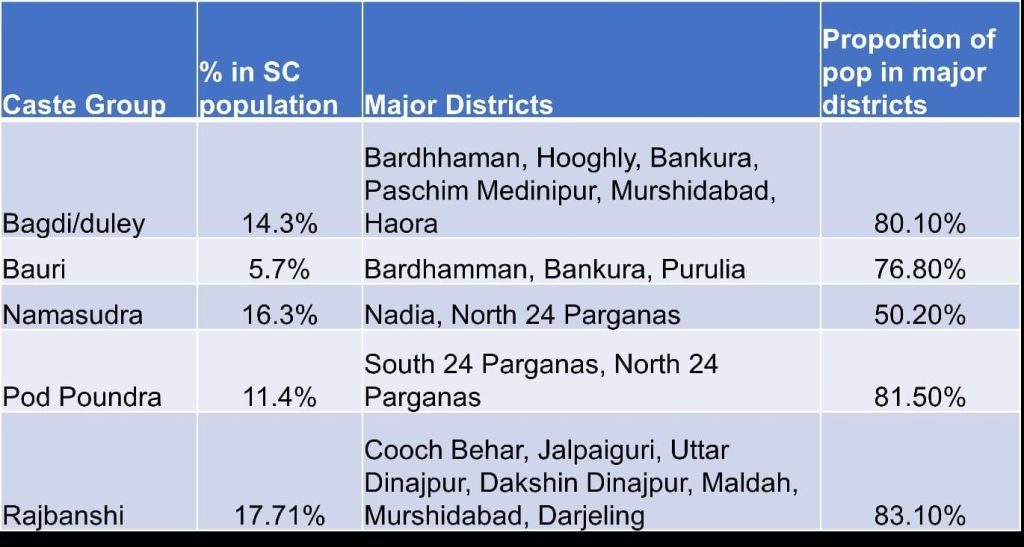

SC communities in Bengal are not homogeneous. They comprise various sub-castes, each with its own set of socio-political challenges. The major sub-castes include the Rajbanshis, Namasudras, Bagdi/Duley, Bauri, and Pod Poundra, among others. These groups are geographically concentrated in different parts of the state, and their political behavior is influenced by their unique histories and economic conditions.

Urban-Rural Divide: Disparities in SC Population Distribution

One of the most striking aspects of SC population distribution in West Bengal is the urban-rural divide. Kolkata, the state capital and economic hub, has a relatively low SC population (5.38%), while the state average stands at 23.51%. This disparity reflects a larger pattern of socio-economic inequality between rural and urban SC communities. Rural SCs are often concentrated in districts with fewer economic opportunities and lower access to education, healthcare, and employment.

The low SC population in Kolkata is indicative of the limited social mobility available to these communities. Urban centers like Kolkata offer better access to education, jobs, and infrastructure, but SCs remain underrepresented in these areas. This can be attributed to historical barriers that have prevented SC communities from accessing education and economic resources. The exclusion of SCs from the benefits of urbanization and economic growth in Bengal is a significant issue that has been overlooked in the state’s development discourse.

Moreover, the disparity between the SC population in Kolkata and the state average suggests that SC communities have largely been left out of the opportunities generated by economic development in Bengal’s urban areas. The economic policies of both the Left Front and the Trinamool Congress (TMC) have failed to address this urban-rural divide adequately. Political parties need to focus on creating inclusive policies that bridge this gap and provide SCs with greater access to opportunities in urban centers.

Historical Context: The Bengal Renaissance and SC Marginalization

To understand the marginalization of SC communities in Bengal, it is essential to examine the region’s socio-political history, particularly during the Bengal Renaissance and the British colonial period. The Bengal Renaissance, which took place in the 19th and early 20th centuries, is often celebrated as a period of intellectual awakening and social reform. However, this movement was largely an upper-caste phenomenon, dominated by the Brahmins and the Bhadralok (the educated, upper-caste elite). SC communities were notably absent from the leadership and intellectual currents of the Bengal Renaissance.

The exclusion of SCs from the Bengal Renaissance can be traced back to the British colonial administration’s land policies. Under the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793, the British introduced a system where zamindars (landlords) were responsible for collecting taxes from peasants and paying a fixed amount to the British government. These zamindars were primarily from upper-caste backgrounds, and the wealth they accumulated through land ownership enabled them to access English education and the cultural capital that came with it.

In contrast, SC communities, many of whom were landless laborers or small peasants, were excluded from these economic and educational opportunities. They remained economically vulnerable and socially marginalized, which limited their participation in the socio-political reforms of the time. The benefits of the Bengal Renaissance, such as increased access to education and social mobility, were concentrated among the upper castes, while SCs continued to be relegated to the periphery of Bengal’s socio-economic fabric.

The legacy of the Bengal Renaissance and the Permanent Settlement Act still resonates in contemporary Bengal. SC communities, particularly in rural areas, continue to face significant barriers to education, employment, and economic advancement. These historical inequities have shaped the current socio-economic landscape of SC communities and remain a major factor in their political marginalization.

Major SC Sub-Castes in West Bengal and Their Geographic Concentration

West Bengal’s SC population is composed of several major sub-castes, each with its own socio-political challenges and geographic concentration. Understanding the distribution and specific issues faced by these sub-castes is critical to comprehending the broader dynamics of caste politics in Bengal.

1. Rajbanshis: The Rajbanshis are the largest SC sub-caste in Bengal, constituting 17.71% of the SC population. They are predominantly concentrated in the northern districts of Cooch Behar, Jalpaiguri, and Uttar Dinajpur. These districts have a high concentration of Rajbanshis, with 83.10% of their population residing in these areas. The Rajbanshis have a distinct ethnic identity and have been advocating for a separate state, claiming that their traditional lands have been encroached upon by other communities. Their demand for statehood reflects their desire for greater political autonomy and recognition.

2. Bagdi/Duley: The Bagdi/Duley sub-caste makes up 14.3% of the SC population and is mainly concentrated in districts like Bardhaman, Hooghly, and Bankura. Historically, the Bagdi/Duley have been landless laborers and continue to face significant socio-economic challenges, including poverty and lack of access to education and healthcare.

3. Bauri: The Bauri sub-caste, which constitutes 5.7% of the SC population, is also concentrated in Bardhaman and Bankura districts. Like the Bagdi/Duley, the Bauri community has historically faced socio-economic marginalization, and their political behavior is influenced by their economic struggles and lack of access to resources.

4. Namasudras: The Namasudras make up 16.3% of the SC population and are primarily located in southern districts like South 24 Parganas and Nadia. Many Namasudras migrated to Bengal from present-day Bangladesh during the Partition and have faced issues related to citizenship and refugee status. Their political mobilization has often centered around these concerns, and their voting patterns reflect their desire for political representation and protection of their rights.

5. Pod Poundra: The Pod Poundra sub-caste is another significant SC group, with a presence in several districts across the state. Like other SC communities, the Pod Poundras face challenges related to land ownership, poverty, and lack of access to social services.

The geographic concentration of SC sub-castes is a critical factor in Bengal’s electoral landscape. Political parties seeking to mobilize SC voters must consider the specific needs and concerns of each sub-caste, as well as the unique socio-political dynamics of the districts in which they are concentrated. Understanding these complexities is essential for any party aiming to gain support from SC communities in West Bengal.

The Rise of Caste Politics in West Bengal: From Left Front Rule to Present

Caste was not always a dominant factor in West Bengal’s political discourse. During the three-decade-long rule of the Left Front (1977–2011), class-based politics took precedence over caste. The Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)) and its allies promoted a Marxist ideology that emphasized the economic struggle between the working class and the capitalist class, downplaying caste as a social and political factor. The Left’s focus on land reforms, particularly through Operation Barga, benefited many lower-caste communities, including SCs, by securing land rights for sharecroppers.

The Left’s class-based narrative also fostered a sense of secularism, with the party presenting itself as a champion of the working class, transcending caste lines. However, this approach came at a cost: caste-based grievances were often ignored, and SC communities’ specific socio-political issues were left unaddressed.

The decline of the Left Front, beginning in the late 2000s, marked a significant shift in West Bengal’s political landscape. The rise of the Trinamool Congress (TMC) under Mamata Banerjee and the entry of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) into Bengal politics brought caste into sharper focus.

1. Erosion of Class-Based Politics: As the Left Front’s influence waned, caste-based identities began to gain prominence. The TMC’s populist approach, which was less ideologically driven than the Left’s class-based narrative, created a political vacuum that allowed caste politics to emerge. The weakening of class-based politics created space for caste-specific issues to come to the forefront, and political parties began to recognize the electoral importance of addressing these grievances.

2. The Rise of the BJP: The BJP’s entry into Bengal’s political landscape significantly altered the state’s caste dynamics. Unlike the Left, which largely ignored caste-based mobilization, the BJP actively sought to engage with marginalized communities, particularly the SCs. The BJP’s outreach efforts focused on SCs in districts where they form a significant portion of the population. The party’s success in these districts during the 2021 Assembly elections reflects this strategic shift.

The BJP’s Hindutva ideology also played a role in mobilizing SC communities. While the BJP historically catered to upper-caste Hindu voters, it has increasingly sought to expand its base by addressing the concerns of marginalized groups, including SCs. By focusing on issues such as citizenship, refugee status, and economic empowerment, the BJP was able to resonate with specific SC sub-castes like the Namasudras and Rajbanshis.

3. Caste-Specific Issues and Identity Politics: As caste politics gained prominence, specific issues faced by various SC sub-castes became central to political mobilization. For example, the Namasudras, many of whom are refugees from Bangladesh, have long struggled with citizenship concerns. The BJP capitalized on this by positioning itself as a defender of Hindu refugees through its support for the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). This alignment with the Namasudra cause helped the BJP secure significant support from the community in the 2021 elections.

Similarly, the Rajbanshis have advocated for a separate state in northern Bengal, citing historical grievances and economic marginalization. The BJP has sought to engage with the Rajbanshi community by supporting their demand for greater political autonomy. The party’s success in Rajbanshi-dominated districts, such as Cooch Behar and Jalpaiguri, is a testament to the efficacy of this strategy.

The growing demand for separate statehood and affirmative action among various caste groups has also fueled caste-based mobilization. The weakening of the Left’s class-based narrative opened the door for these demands to gain political traction, with parties like the BJP and the TMC recognizing the need to address them directly.

4. Economic Disparities and Caste: Despite the Left Front’s land reforms, significant economic disparities remain, particularly in rural areas where SC communities are concentrated. These disparities often align with caste lines, with certain lower-caste groups continuing to experience high levels of poverty and marginalization. As SC communities became more politically aware, caste-based grievances related to economic inequality began to emerge as a critical factor in Bengal’s political discourse.

Electoral Impact: SC Population and BJP’s Performance in the 2021 Assembly Elections

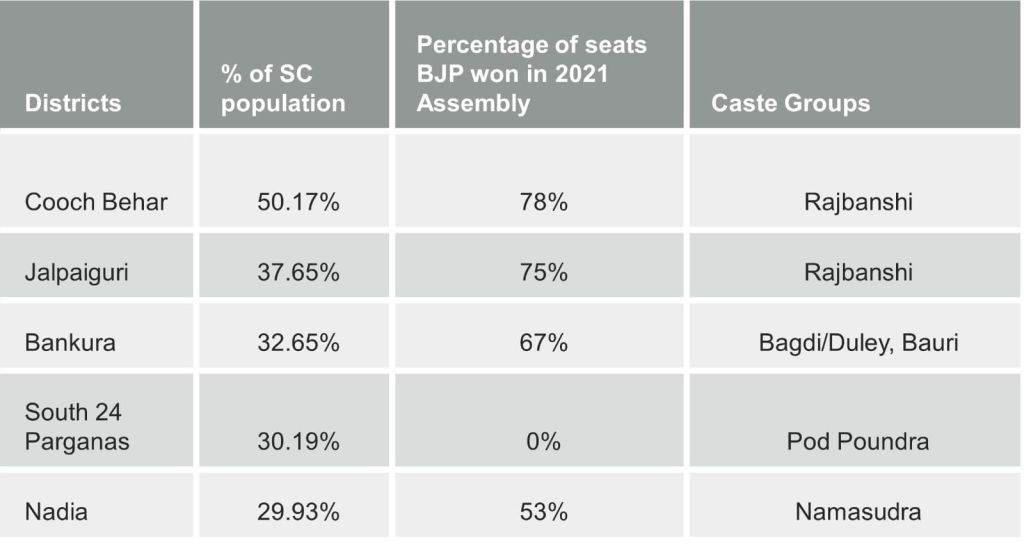

The 2021 West Bengal Assembly elections marked a turning point in the state’s caste politics, with the BJP making significant inroads in SC-dominated districts. The chart below provides a deeper insight into the electoral implications of the SC population distribution, focusing on the 2021 Assembly elections and the BJP’s performance.

In districts with high SC populations, such as Cooch Behar (50.17% SC) and Jalpaiguri (37.65% SC), the BJP performed exceptionally well, winning 78% and 75% of the seats, respectively. These numbers demonstrate the strong correlation between the SC population percentage and the BJP’s electoral success in these districts. The party’s ability to mobilize SC voters in these areas was a result of its targeted outreach efforts and its emphasis on addressing SC-specific issues.

Interestingly, in districts like South 24 Parganas, where the SC population is 30.19%, the BJP did not win any seats. This anomaly highlights the unique socio-political dynamics of the district, where caste and religious factors intersect. South 24 Parganas has a large Muslim population, and the TMC’s stronghold in the district is partly due to its ability to navigate the complex interplay of caste and religion.

The BJP’s focus on SCs, particularly in northern Bengal, paid off electorally. However, the party’s inability to make similar gains in other SC-dominated areas like South 24 Parganas points to the limitations of a purely caste-based strategy. Localized issues, entrenched political networks, and the dominance of other parties also play a significant role in determining electoral outcomes.

The Role of the Trinamool Congress (TMC) in Caste Politics

While the BJP made significant gains in SC-dominated districts, the Trinamool Congress (TMC) remains a formidable force in West Bengal politics. Under Mamata Banerjee’s leadership, the TMC has sought to maintain its dominance by appealing to various marginalized communities, including SCs. The TMC’s populist governance style, which emphasizes welfare schemes and subsidies, has helped it retain support among rural voters, including SCs.

However, the TMC’s approach to caste politics has been less explicit than the BJP’s. The TMC has traditionally relied on a broad-based populist strategy, focusing on economic development and social welfare rather than identity politics. This approach has been successful in many areas but has left space for the BJP to make inroads among SC voters by directly addressing caste-specific issues.

In response to the BJP’s rise, the TMC has begun to pay more attention to caste-based concerns. For instance, the TMC has increased its outreach to SC communities through targeted welfare programs and affirmative action policies. The party has also emphasized its commitment to secularism, positioning itself as a counterweight to the BJP’s Hindutva agenda.

Caste Politics Beyond the 2021 Elections

The rise of caste politics in Bengal is not merely a symptom of electoral change but a reflection of deeper socio-political shifts within the state. As caste-based identities gain prominence, political parties must adapt their strategies to address the specific needs of marginalized communities, particularly SCs.

For the BJP, the 2021 elections demonstrated the potential of caste-based mobilization. However, the party’s long-term success in Bengal will depend on its ability to balance caste politics with other factors, such as economic development and communal harmony. The BJP’s strategy of appealing to SC voters through both caste and religious identity has been effective in some areas but has limitations in regions where caste intersects with other complex socio-political factors.

The TMC, meanwhile, faces the challenge of maintaining its broad-based populist appeal while addressing the growing importance of caste. The party’s ability to retain SC support will hinge on its capacity to deliver tangible economic benefits to marginalized communities and respond to caste-based demands without alienating other segments of its voter base.

Conclusion

Caste politics in West Bengal has evolved significantly over the past decade, moving from the margins of political discourse to the center of electoral strategy. The rise of the BJP, combined with the decline of the Left Front and the populist governance of the TMC, has brought caste-specific issues to the forefront of Bengal’s political landscape. SC communities, in particular, have emerged as a crucial constituency for political parties seeking to consolidate power in the state.

The urban-rural divide, the historical marginalization of SC communities, and the unique socio-political challenges faced by different SC sub-castes continue to shape Bengal’s caste politics. Political parties that wish to succeed in Bengal must understand the complex interplay of caste, class, and identity, and develop inclusive policies that address the specific needs of SC communities.

As West Bengal continues to evolve politically, caste politics will remain a key factor in determining the future course of governance and development in the state. The 2021 Assembly elections were a clear indication that caste-based mobilization is becoming an increasingly important tool for political parties. Understanding the socio-economic conditions, historical grievances, and unique challenges of SC communities will be essential for any party seeking to navigate Bengal’s complex political landscape in the years to come.